Sicily

With total vineyard area reduced to just over 125,000 ha/312,500 acres, Sicilia's annual wine production averaged 7 million hl/185 million gal between 1999 and 2003. This decline in production from its old volumes of 10 million hl is attributable to a fall in demand for the sort of blending wines in which Sicilia excels: deep-coloured, high-strength wines that were used to bolster feebler efforts from more northerly climes, not only within Italy.

The island's geography and climate—a hilly and mountainous terrain with poor soil, intense summer heat, and low rainfall—make it ideal for the classic Mediterranean agriculture of grain, olive oil, and wine, and Sicilia's viticulture, in fact, enjoys a series of natural advantages which have not yet been fully exploited: hillside vineyards with excellent exposures, abundant sunlight, and high temperatures to ripen the grapes; excellent elevation (it is by no means unusual to find a flourishing vineyard at 500 to 900 m/1,640–2,950 ft above sea level); good diurnal temperature variability; and a range of native vine varieties with real personality. The concentration on quantity over quality, systematically encouraged by the regional government's subsidies for the transformation of the traditional gobelet training systems into more productive wire-trained or tendone systems between 1960 and 1987, has done no small harm to Sicilian viticulture and has led to a chronic cycle of over-production, declining prices, and wines which are impossible to market.

Things started to change in the late 1990s. By the mid 2000s, about 90,000 ha of the island's vineyards were Guyot trained, while 14,700 ha were still alberello (bush vines), and 15,650 ha were tendone trained. The fact that over 70 per cent of Sicilia's vines are now wire trained illustrates a move to mechanization, and a readiness to start addressing high production costs. In addition, investment by producers in northern Italy such as Zonin, Girelli, and G.I.V. has shown the promise that exists, and the work of consultants such as Alberto Antonini, Riccardo Cotarella, and Carlo Ferrini has resulted in the production of some impressive wines from Sicilian-owned wineries Baglio Curatolo, Morgante, and Donnafugata respectively.

Despite all this, doc production is still low, usually no higher than 2 per cent of total wine production as many producers prefer to use the IGT Sicilia denomination, as it allows greater flexibility. Significant producers include négociant Duca di Salaparuta winery, whose Corvo brand was for years one of Italy's most prominent, Regaleali, and Planeta, one of Sicilia's huge success stories in recent years. Its owner, Diego Planeta, is also the president of Settesoli, Sicilia's most important co-operative winery, and has done more than most to present the modern face of Sicilian wine to the world.

Most of these producers have drawn on Sicilia's wealth of indigenous grape varieties. Catarrato is the island's most widely planted grape variety, accounting for about 38 per cent of plantings. Its presence accounts for the large production of grape concentrate that Sicilia still produces and exports to the rest of Italy (chaptalization is not permitted in Italy, but grape concentrate is used for enrichment by the majority of Italian producers). Inzolia, which accounts for about 7 per cent of Sicilia's area under vine, has the potential to produce attractive and modern wines, as does Grillo whose 2,300 ha represent less than 3 per cent of plantings. Chardonnay is the most popular of the imported varieties, with 3,637 ha of vineyard, but even the most expensive bottles suggest that the vine has found it just too hot in Sicilia. On the whole, however, Sicilia's white wines have improved dramatically in recent years, as advances in the cellar have ensured that the flavours captured in the grapes are preserved by the use of protective measures such as refrigeration, rather than dissipated or oxidized, as once was the case.

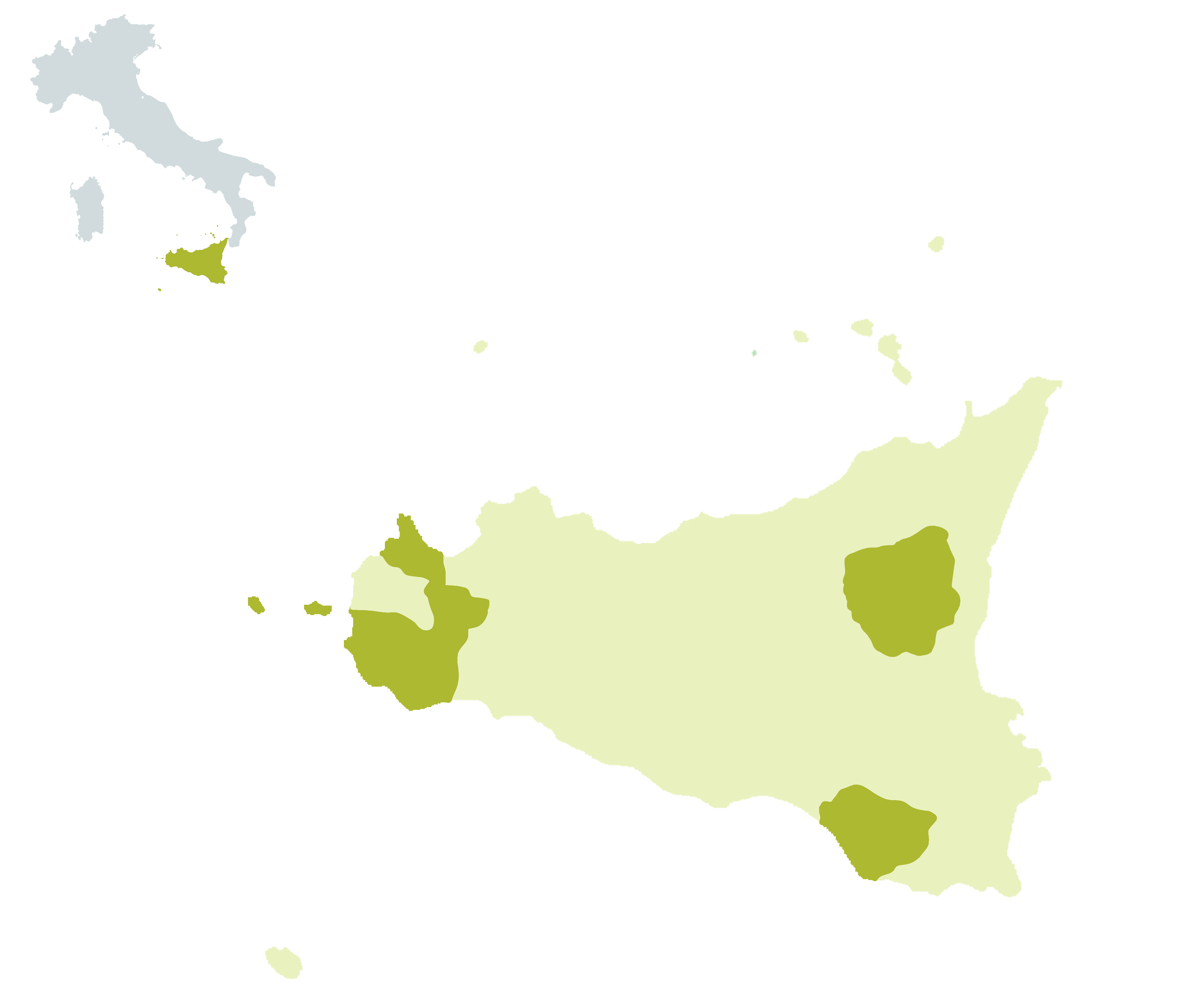

Of the red varieties, Nero d'Avola, accounting for 13 per cent of total vineyard, is the most exciting. Its deep colour and robust tannin structure has long made it a favourite of blenders, but it is now staking a claim as a Sicilian classic varietal. Attention seems destined to turn to Perricone and Nerello Mascalese to see if by any chance either can rival Nero d'Avola. Syrah, a variety similar in many respects to Nero d'Avola, seems ideally suited to the climate in central Sicilia, and is already producing very exciting wines from some of the 4,400 ha planted. As with Chardonnay, Sicilia just seems too hot for the likes of Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon.

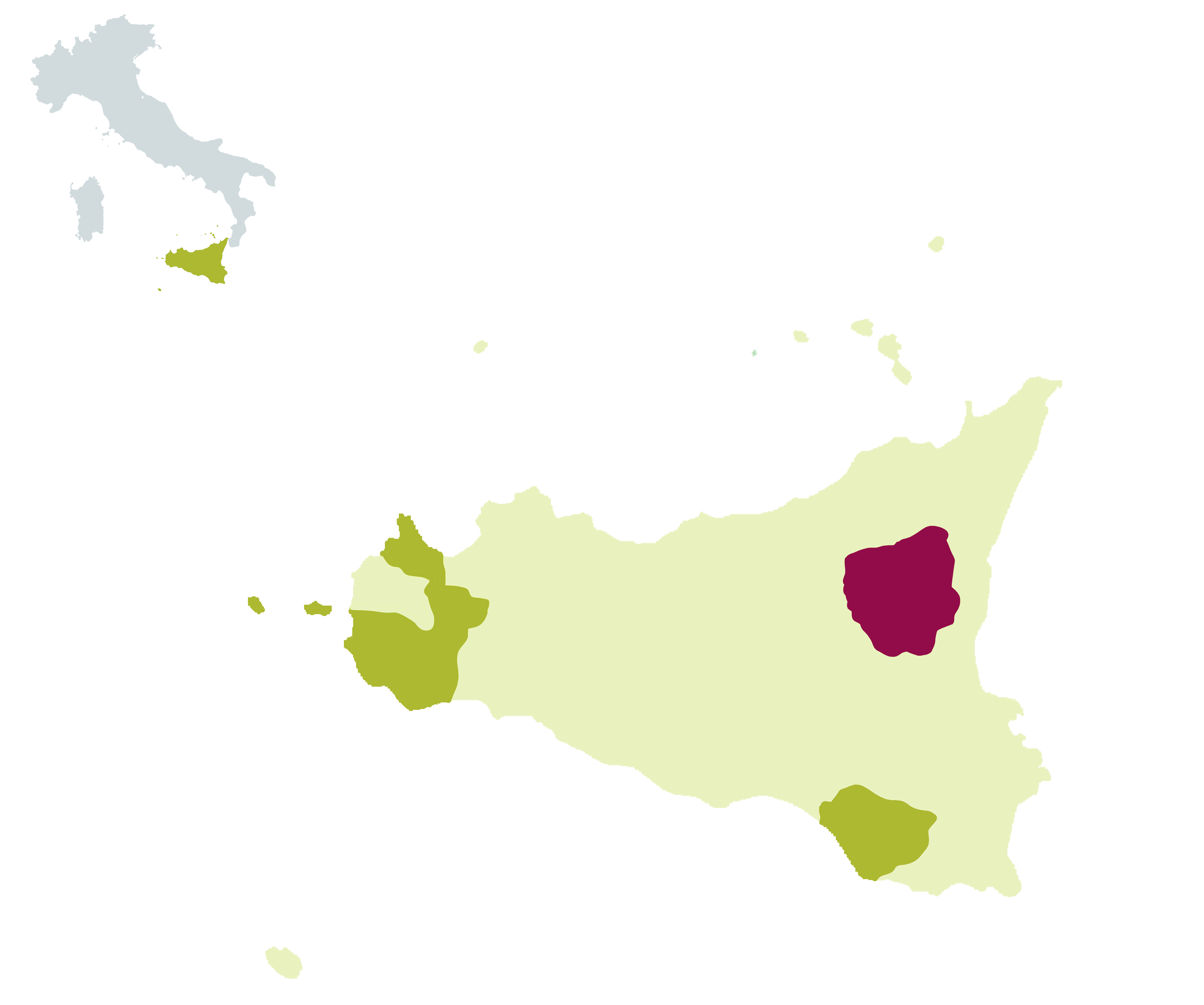

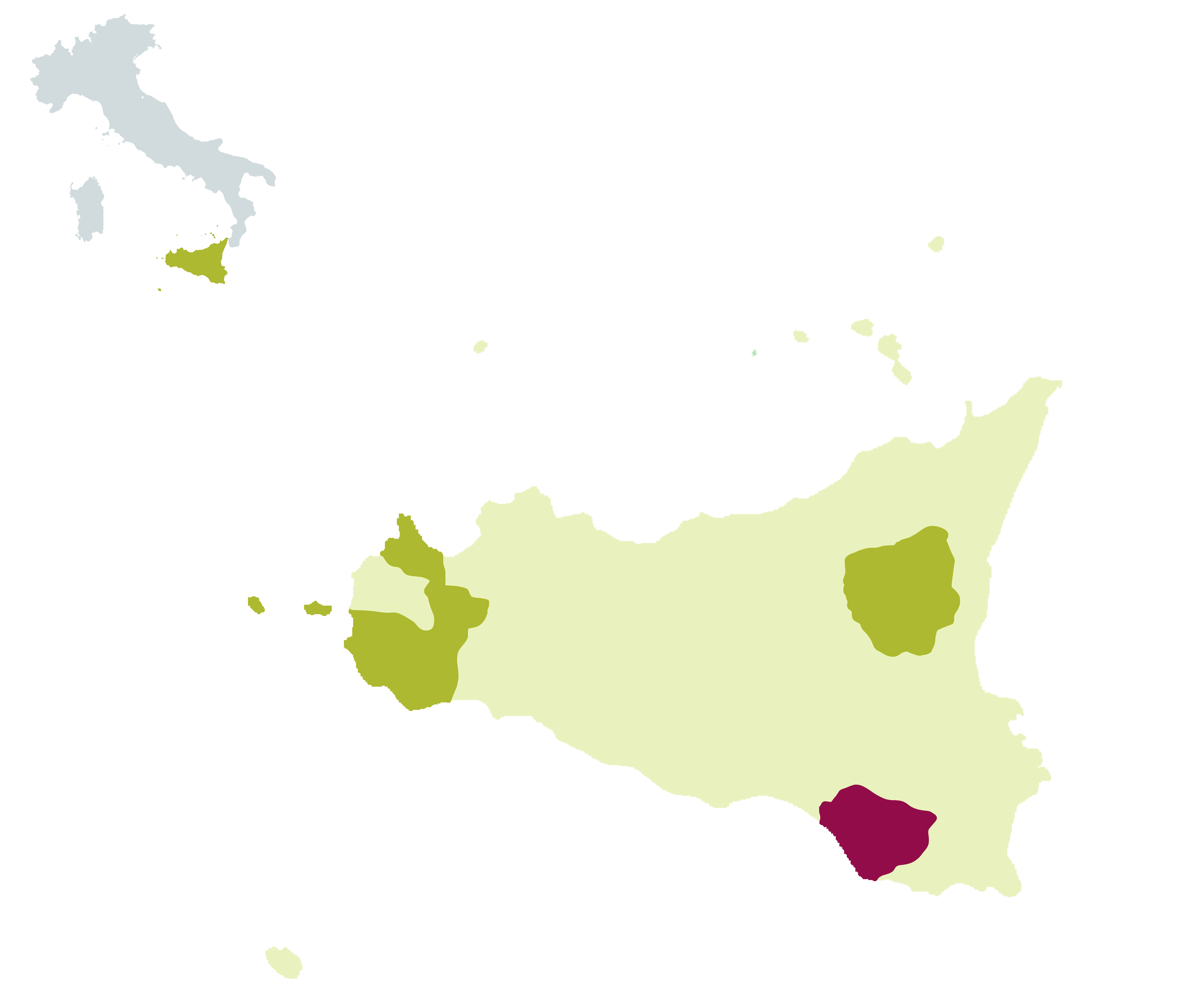

In the southeast of the island, Cerasuolo di Vittoria, made from a blend of at least 40 per cent of Frappato and no more than 60 per cent of Nero d'Avola (here known as Calabrese), has improved in recent years. In the north east, much attention has been focused on planting vineyards on the higher slopes of Mount Etna in the belief that the volcanic soil and high altitude will combine to produce great wines. Early efforts show promise.

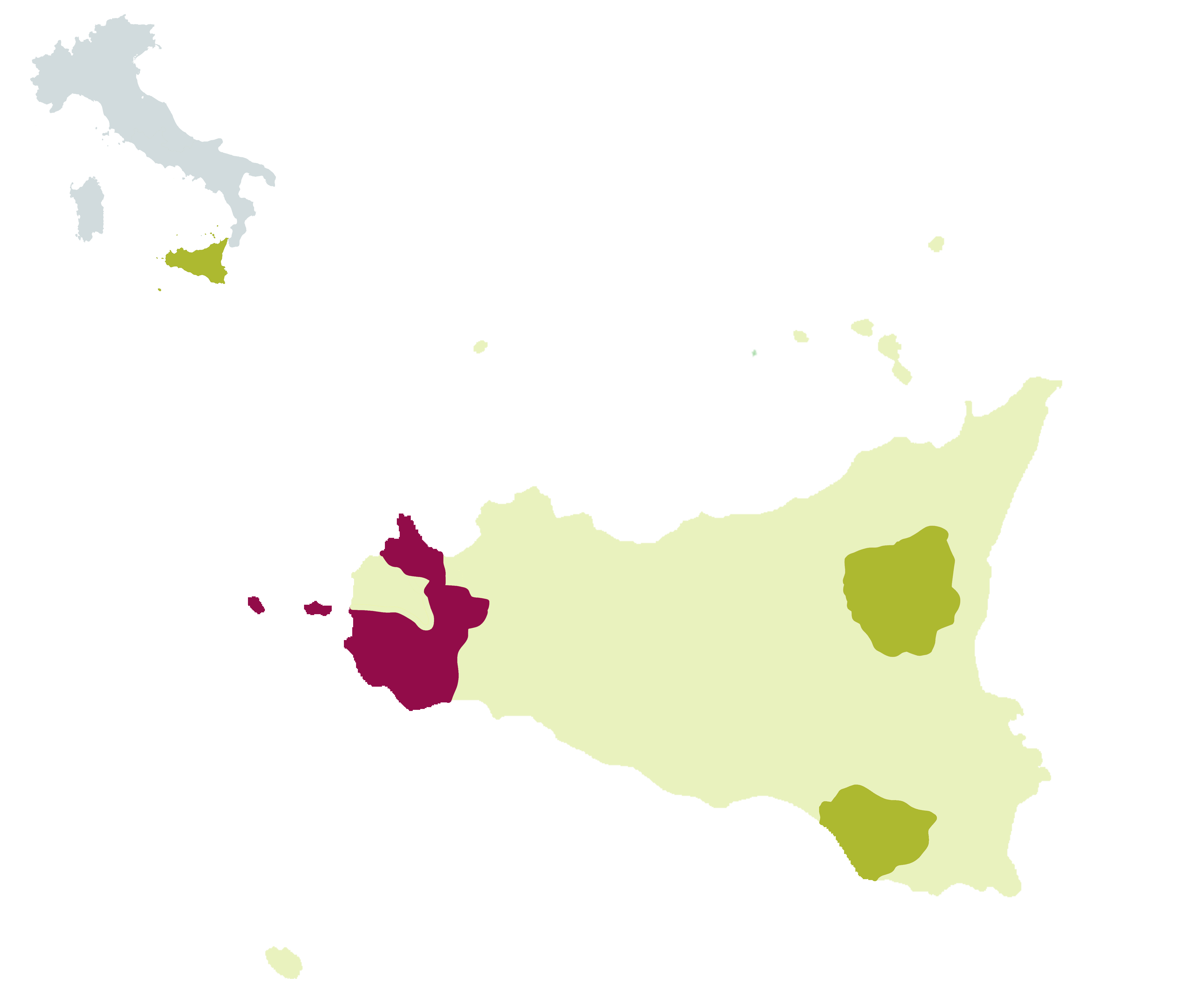

Sicilia once enjoyed a great reputation for sweet wines, and attempts to revive the tradition are currently under way, although the once famous Moscato of Siracusa seems irremediably extinct, and Moscato of Noto, despite attempts to revive it, on the verge of becoming so. Moscato of Pantelleria returned to the market with convincing evidence of its inherent quality, and the Malvasia delle Lipari of the late Carlo Hauner which emerged in the 1980s has demonstrated that the reputation of this wine was not entirely mythical either. Today the Barone di Villagrande winery is building on the work done by Hauner.

References:

, Vino Italiano: The Regional Wines of Italy (New York, 2002).

, From Brunello to Zibibbo: The Wines of Southern Italy (London, 2001).